Assessing respondent-driven sampling

Sharad Goel and Matthew Salganik, 2010

This paper uses simulations drawn from known network populations to assess the statistical properties of respondent-driven sampling (RDS) estimators. The basic estimator under examination here is:

\[ \hat{\mu}_f = \frac{1}{\Sigma_{i = 1}^n 1/degree(X_i)}\Sigma_{i = 1}^n\frac{f(X_i)}{degree(X_i)} \]

This is just the mean of \(f(X_i)\) where each person, \(X_i\) is weighted in inverse proportion to their degree. So high-degree individuals are weighted down because they are probably oversampled in the RDS, and vice versa for low degree individuals. If \(f(X_i)\) is a binary variable like whether or not a respondent has some disease, then \(\mu_f\) is the proportion of the population with that disease. Theoretically, this estimator is unbiased given that a certain set of assumptions hold true.

The authors construct simulations which draw sub-samples from the Project 90 and Add Health surveys. Project 90 is a longitudinal survey from the late 1980s, meant to study the role of network structure spreading infectious diseases. Add Health, or more formally the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, tracks the full set of friendship networks between students at a set of high schools across the United States. Each of these samples are fairly large, and draw 500-observation samples from them using simple random sampling (SRS) and RDS network sampling. They can then compare RDS and SRS to the known characteristics of the populations in the data.

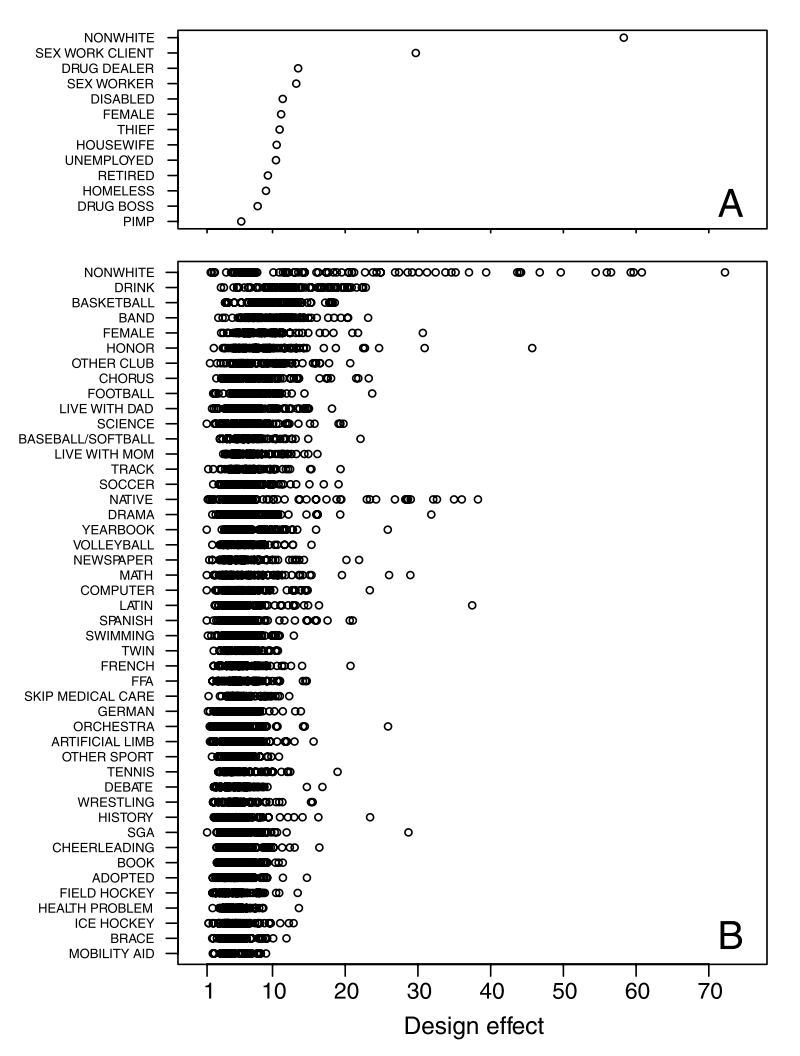

The results are presented as design effects, \(Var(\hat{p}_RDS)/Var(\hat{p}_SRS)\). “A design effect of 10, for example, effectively reduces an RDS sample of nominal size 500 to an SRS sample of size 50” (p.6744).

Here are the design effects for all the rates that the authors estimate:

It’s clear the result of the exercise is that, for every parameter the authors want to estimate, the variance across RDS samples is higher than across SRS samples, often by many times. The paper goes on to show that the confidence intervals for RDS estimates appear too small, since they only overlap with the true value between 42% and 65% of the time, when they should always overlap 95% of the time. They also show that re-weighting of the RDS sample according to degree largely does not do much to improve the estimator: The estimation errors produced by the RDS estimator are highly correlated with the errors that would emerge if those same data were treated as if they were from an SRS. This suggests that degree imbalance may not be so central to the performance of the estimator. Instead, reducing the sampling variability should instead be the main objective for methodological researchers.

Overall, this paper paints a scary picture of RDS as a tool hailed as the key to accessing vulnerable, hard to reach populations. Even under simulated conditions where all assumptions are met, the estimates produced from any given sample may veer quite far from the truth about the population.