Neighborhood choice and neighborhood change

Elizabeth Bruch and Robert Mare, 2006

This paper takes aim at Schelling’s seminal agent-based models that showed how segregation results from individual choices of neighborhoods. First, a brief background on the Schelling model:

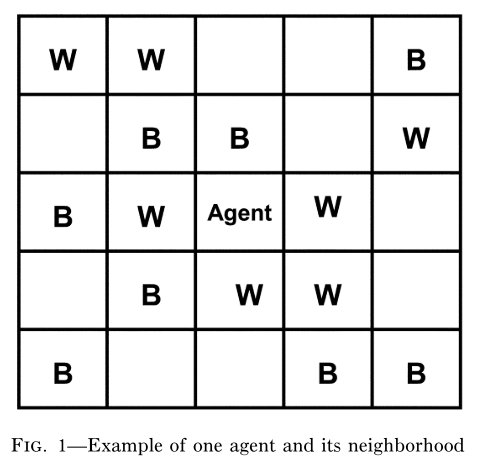

Schelling’s model sets up a grid of black and white dots like a checkerboard. Here’s an image of small section of such a grid, focused on one agent and their surroundings.

Schelling sets off a simulation meant to determine the consequences of white flight for segregation. Basically, he assumes that whites start wanting to move out of their current location on the grid when their immediate neighborhood becomes minority-white. Starting from this ‘choice function’, he simulates a number of iterations on the grid, where each iteration involves a randomly selected white or black dot making a choice about whether or not to move. The simulation plays out and leads to increased segregation. The conclusion, then, is that micro-level decisions by families and households to seek out neighborhoods where they are the majority group yields macro-level segregation.

Bruch and Mare’s response

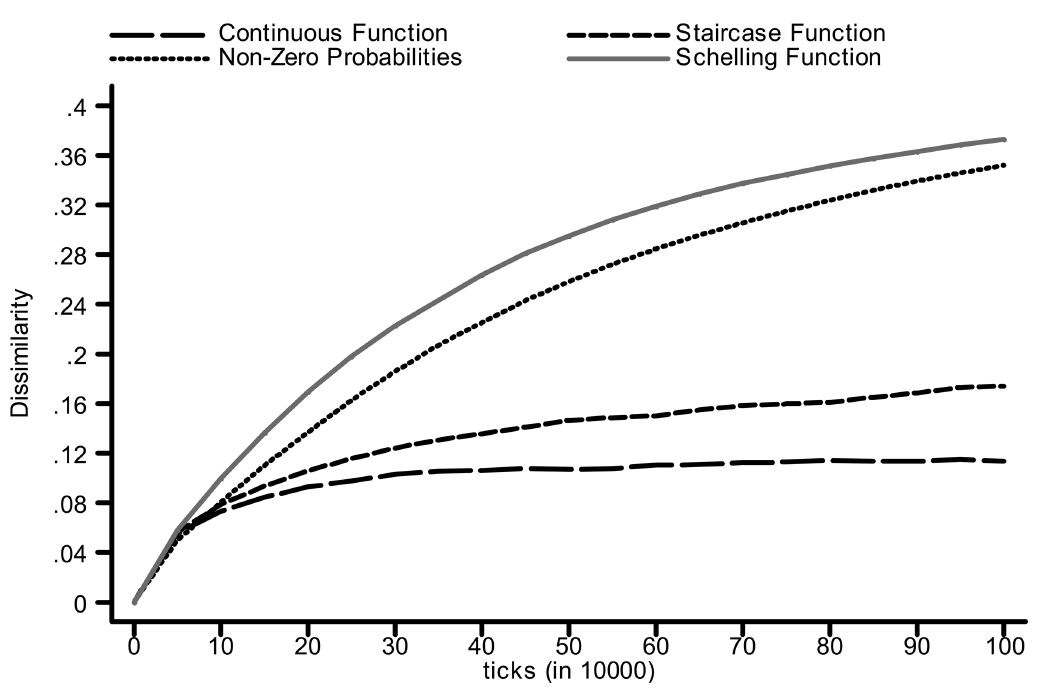

The thrust of Bruch and Mare’s paper is to evaluate the sensitivity of Schelling’s result to the shape of the choice function. Bruch and Mare set up a similar simulation and run it several times, each with a different choice function to define how the agents make their decisions. They observe how segregation changes over time in each case. Here are the different choice functions they assess:

And here is how segregation changes over time in each case:

The key takeaway from these plots is that the validity of Schelling’s conclusion about the inevitability of segregation really depends on the choice function that’s assumed. If we think that a white person’s preference for their neighborhood shifts as soon as they become a minority, Schelling’s conclusion holds. If, instead, their preferences are a linear function of their own neighborhood representation, Bruch and Mare show that this leads to much lower levels of segregation.

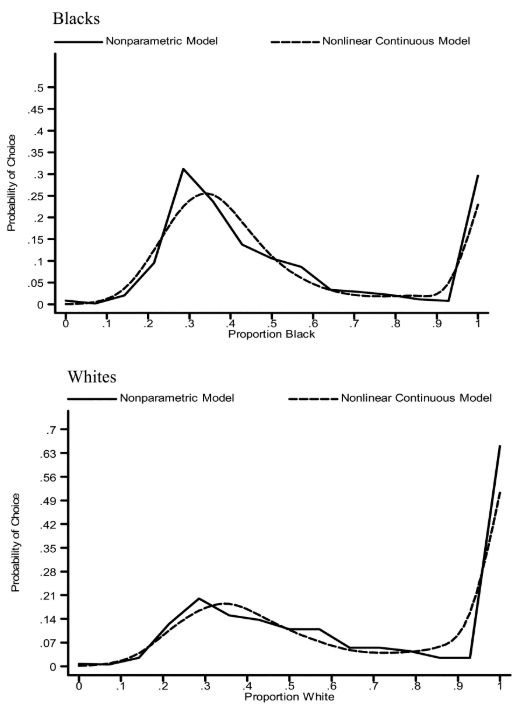

The next logical question is: What do people’s choice functions really look like? Bruch and Mare use survey data that asks respondents to rate their neighborhood preferences to back out empirical choice functions and plot them. In particular, they seek any sign of a threshold in the choice function that would support Schelling’s choice function. Here are plots of the empirical choice functions:

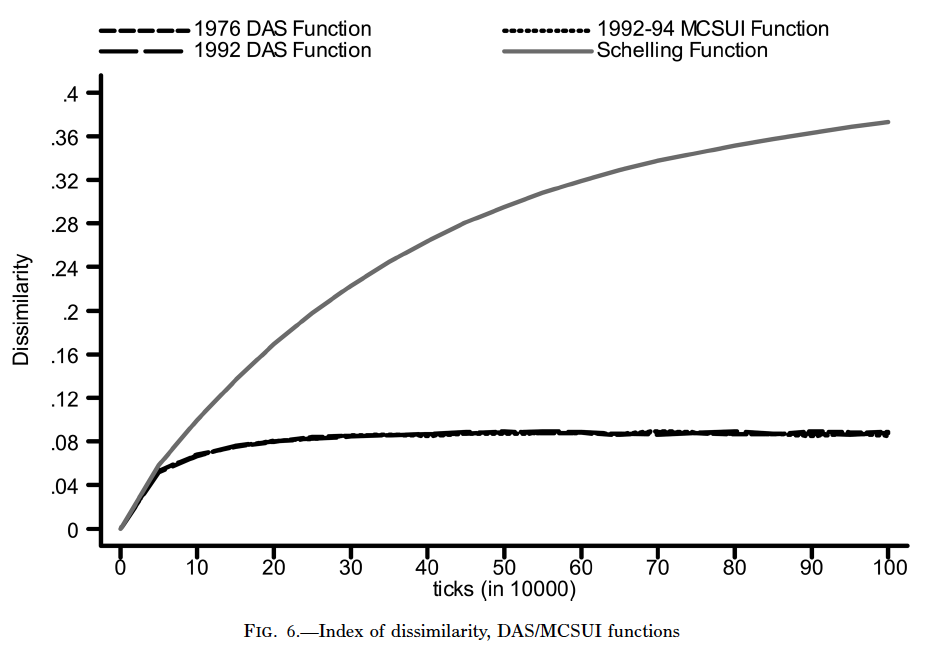

The authors argue that these curves are not indicative of the existence of a threshold, and I’m inclined to agree. Finally, the authors convert these curves into probability distributions and use them as choice functions in the simulation. This yields a simulation where the input parameters are empirically collected. Below are the final results, i.e. what happens to segregation across the grid when using an empirically derived choice function instead of the Schelling step function:

Again, the result is clear. Segregation plateaus quickly in a simulation that reflects people’s self-reported preferences for homes.

This is a very good paper, although there are two issues with it worth mentioning. First, even with empirical choice functions the models still feel a bit distant from reality. As the authors mention throughout the paper, there are many reasons why people make the choices they do when it comes to housing and neighborhoods. This model is hyperstylized and hones in exclusively on the role of neighborhood racial composition. Even then, it never incorporates empirical data on moves.

Second, a response to this paper by Van de Rijt, Siegal and Macy showed quite clearly that, just like Schelling’s conclusions are sensitive to the choice function used, Bruch and Mare’s conclusions are sensitive to the amount of randomness in the model. Basically, they show that segregation only plateaus when the agents’ decisions about whether and where to move are so random that they often move to neighborhoods where they are a smaller minority than where they previously lived. This mechanically reduces segregation and keeps it flat. If agents are instead programmed to move more deterministically to preferred neighborhoods, a continuous choice function does not prevent segregation at all. IF anything, it actually makes it worse.

One clear reason Bruch and Mare are able to advance the Schelling model is that they had greater access to computational resources in the early 2000s than Schelling did in the late 1970s. This makes me wonder if, almost twenty years later, there might be further room to push the envelope.

One can imagine, for instance, using modern spatial analysis tools to replace Bruch and Mare’s grid with something shaped like an actual neighborhood, and using the actual neighborhood boundaries and compositions to initialize the model. One can even think of inputting the actual changes in neighborhood composition between Decennial Censuses and using these changes to back out the underlying choice function. All of these things would be hard, but seemingly within the realm of possibility.